Imagine a rainforest clothed in rising mist. A mystical place filled with life and the calls of many types of birds and animals. Steep verdant hills and valleys, cliff faces drop, splotched in tones of green! The sun rising over the expanse of the Amazon. Splashing water, chimera rainbow hues. Towering ice cap mountain peaks of the Andes stand firm in the west, golden in the morning light. These mountain slopes have given rise to marvelous biological diversity! To understand Cacao, we must understand where she comes from—a place closest to the sun, where day and night are equal in length all year long. A vastly intricate union of thousands of species of plants, animals, insects, birds, fungi.

When I sip Cacao, my heart softens, and I feel a heightened sense of willingness and patience. I can feel how she advocates balance in all my relationships.

Cascading water surges through rocky creeks finding its way to the meandering serenity of the larger rivers below. Palms, and myriad plants and trees with vastly diverse shaped leaves hug the banks. Where Cacao comes from, flowering vines delicately hang over the river’s shores, releasing densely-sweet dew-like nectarous aromas.

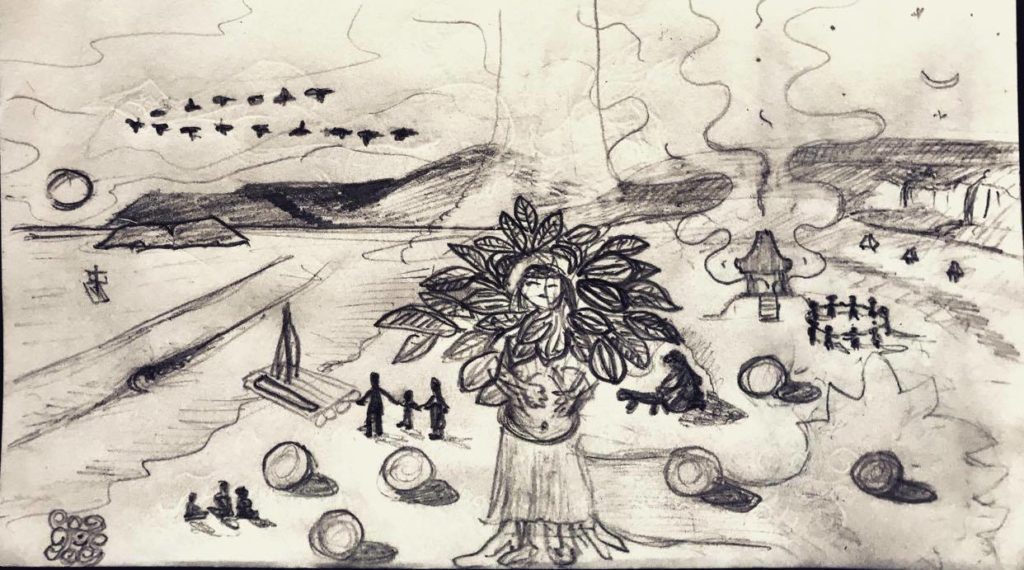

The World Tree and Her Planetary Mission

How can a relatively inconspicuous understory tree be so pregnant with wholesome goodness, so full of virtues, and so charged with mythologies? Why is cacao so revered that it has been used as money, medicine, antioxidant-rich superfood, incense, and for a variety of ceremonial offerings—to invoke responses from supernatural beings; to celebrate special moments and calendar markers such as the solstice and equinox; to sanctify weddings and births; to consecrate times of initiations and rites of passage; and as funeral offerings to accompany the dead on the afterlife voyage? When we stretch our imagination to contemplate ancient creation myths that consider cacao not just a gift from the gods to humanity, but an actual component of our identity as humans, we can begin to understand. In the Popol Vuh, the Quiché Mayan holy book, the gods created humans from Maize and Cacao, along with other foods such as the White Cacao, known as Pataxte, Theobroma bicolor; the Soap Apple, known as Zapote, Manilkara zapota; Hog Plum or Jocote, Spondius purpurea; Golden Spoon, known as Nance, Byrsonima crassifolia; and the White Sapote, that is Matasano, Casimiroa edulis. These narratives speak to the role of plants as an intimate part of the human fabric.

Plants of the Popol Vuh creation myth

Jocote

Nance

Matasano

Cacao – Kakawa

Pataxte – Patas

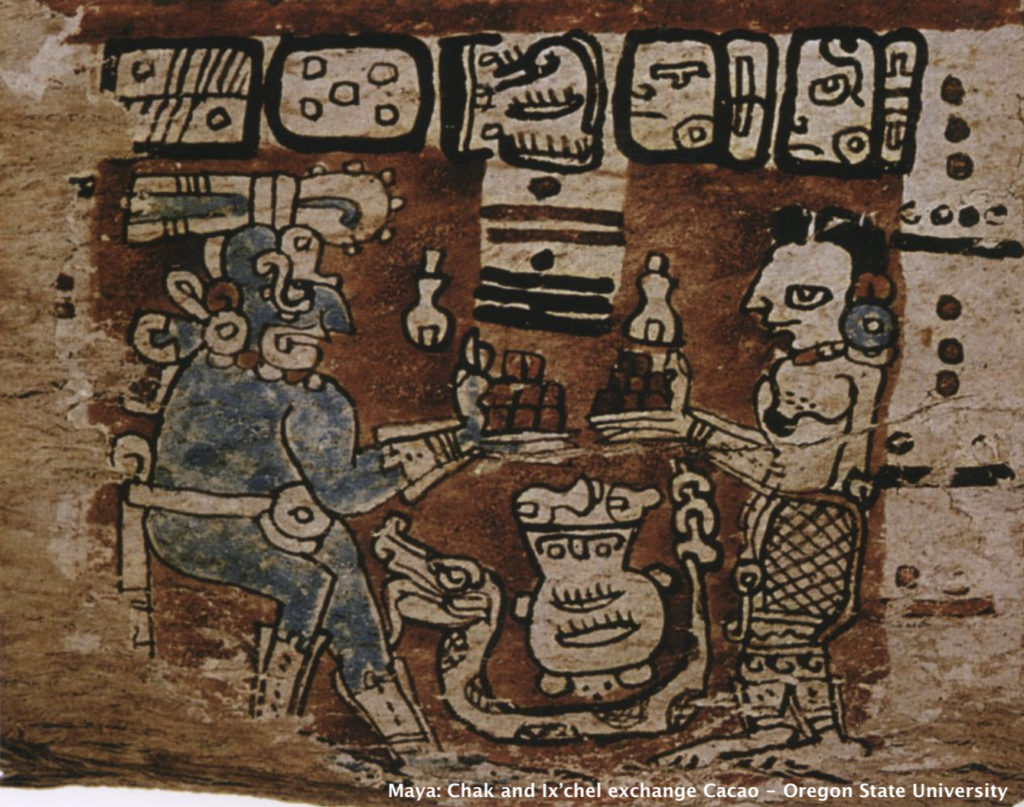

Many other Central American creation myths postulate human origins in Cacao. Ancient pottery depicts the Maya great mother Ix Chel, Lady of Translucent Rainbow Light, goddess of medicine, weaving, fertility, and the crescent moon, exchanging Cacao with the rain god Chaac, the patron of agriculture. Chockablock with history and cultural lore, legends have it that Cacao was gifted to early peoples by Quetzalcoatle, the Feathered Serpent itself, so that we may remain heart-centered and energetic. Cacao is a faithful part of the human-fabric, to such an extent that we may say, “To know thyself, drink Cacao”

This iconography is rooted in the tree’s reputation as a conduit between heaven and earth. To the ancient peoples who grew and adored Cacao, this sacred crop was a Tree of Life uniting the quotidian world with the supernatural realms. The ceremonial consumption and offering of Cacao symbolically connected individuals with the powers that govern their existence, with renewal and rebirth, and with the deities of creation. The bounty of the Cacao tree in Mesoamerica represents abundance, and her rounded fruit symbolize fertility. The deep spiritual meaning of Cacao crystalized her importance in all pre-Colombian societies that knew her. Cacao is a blessed, scrumptious elixir that has shaped and formed societies, igniting creation and urging us to evolve.

Cacao represents the fragile and delicately interconnected web of life, the majesty of biological diversity. She is the emblem for many great cultures. There are many things that she knows…

Don Memo Morales, an elder of the Costa Rican Brunka tribe, once shared a story with me. “After the cataclysm, when the earth was burned by fire, heaven had compassion for humanity, and from the sky dropped seeds of Cacao. From these seeds grew the Cacao tree, and from its ripe pregnant fruit was born the first woman, who gave birth to the first man, and from there the first people came.”

Softly, Memo continued, “In compassion for humanity, the Creator gave the first people three types of Cacao so they could live well: a sweet variety to share and to enjoy in festivals, a simple variety to eat every day as food, and a bitter variety for healing all illness.”

Born at the Summit of Mega Biological Diversity

No other region in the world surpasses northwest South America in biodiversity, which peaks in the “eyebrows” of the Andes. Two mountains—Sumaco, known locally as the most beautiful mountain, and Napo-Galeras, an isolated limestone massif—are considered especially sacred by the region’s diverse indigenous peoples. I devoted four years there that, in 1994, successfully included Napo-Galeras mountain as part of the new Sumaco Napo-Galeras National Park. This effort is shared in my book, Rainforest Medicine – Preserving Indigenous Science and Biodiversity in the Upper Amazon.

In 2010 I participated on a botanical expedition in the Tropical Wet Forest on the eastern slopes of Napo-Galeras, east of the Andes, led by Dr. Carlos Cerón, curator of the herbarium at Ecuador’s Central University, to learn more about wild Theobroma cacao, its mega-biodiverse rainforest setting, and the Malvaceae botanical family that Cacao belongs to. Relatives of this family from other regions include fibrous, stimulant, and mucilage-bearing plants such as Cotton, Okra, Kola nut, Durian fruit, Hibiscus and Mallow.

Cotton

Okra

Cola Nut

Durian

Hibiscus

Mallow var.

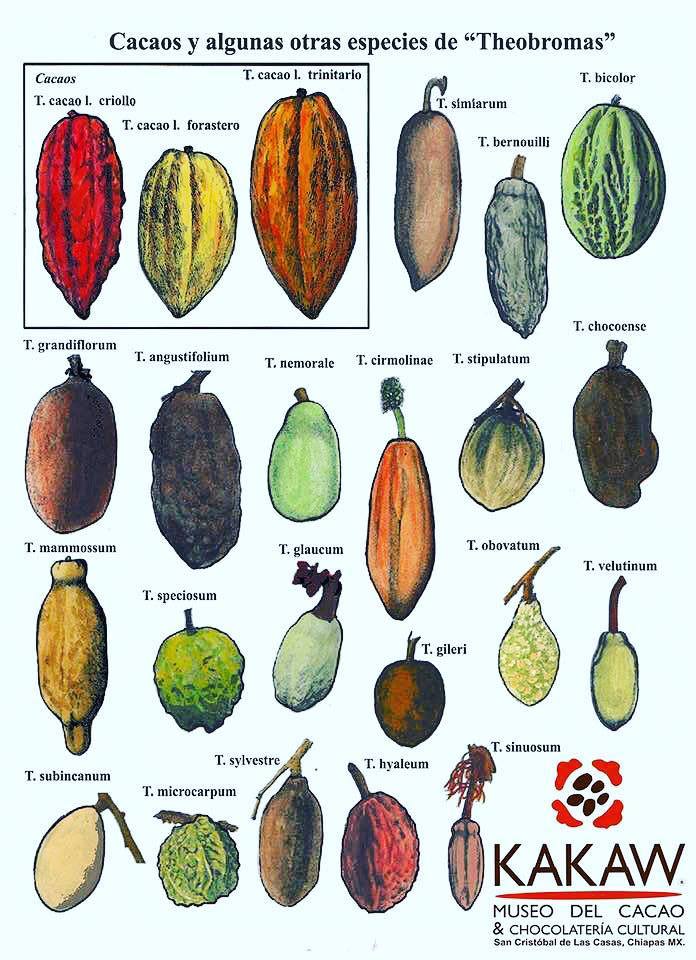

An impressive sight it is to see wild Cacao trees growing in their original setting, surrounded by a remarkably high concentration of related plants: Patas, or White Cacao, Theobroma bicolor, whose edible seeds are used to make chili sauce; T. subincanum, called Cushillu-cambiac, with deliciously aromatic edible pulp; and the famed T. grandiflorum, called Cupuassu in Brasil, similarly prized for its nectarous pomace. As we explored the forest collecting hundreds of botanical specimens, pressing plants late into the night, and collecting botanical information, more related species came to light. These were trees in the genus Matisia and Quararibea, both with fine edible fruits known as Sapote, and Herrania, a close cousin of Cacao, locally known asCambiac, distinguished by saturated maroon flowers with remarkably elongated petal-appendages and fine sweet-flavored pulp held in petite deeply furrowed pods. Its young leaves are used medicinally, macerated in water to release mucilage, drunk to relieve constipation. We were not aware yet of the discovery we were about to make.

Cacao and relatives we encountered

Theobroma cacao

Theobroma bicolor

Theobroma subincanum

Theobroma grandiflorum

Matisia sp.

Matisia sp.

Matisia cordata

Herrania nitida

Herrania purpurea

Cacao has a fascinating natural history. Squirrels, the Tayra, a large, tree-dwelling weasel, and tropical relatives of the Raccoon, such as the Kikanjou, the Bushy-Tailed Olingo, and the elusive Cacomistle all feast on Cacao. While many mammals disperse Cacao seeds—particularly the Saddleback Tamarin, a species exclusive to the Tropical Wet Forest, the sharp-witted White-Fronted and Brown Capuchin Monkeys, the Squirrel Monkey, the graceful Woolly Monkey, and elegant Spider Monkey all feast on Cacao. Though thousands of insect species live in Cacao’s environment, few pollinate her. Due to the evolution of Cacao’s complex floral structure, her pollinators are highly restricted to tiny mosquito-like insects called midges, perfectly shaped to enter and pollinate Cacao’s small bone-white flowers that appear on the trunk and branches amidst the moist and cool lower level of the rainforest.

Bushy-Tailed Olingo

Cacao midge (amplified)

Spider Monkey

Flowers of Cacao

Cacao flower (byAndreas Kay)

The Tropical Wet Forest is a festival of biodiversity, and soon our makeshift collection table overflowed with fruits and seed gathered on jungle forays. Cacao relatives growing in the region include the mighty silk cotton Kapok, the Ceiba pentandra, known locally as Uchuputu, a tree charged with mythology whose powerful outreaching branches offer habitat for worlds of life above the forest canopy; Kamotoa, a towering emergent tree with elegant buttress roots that was assigned its botanical name only later, in 2012, Gryanthera amphibiolepis, that today is sadly vanishing due to unregulated and illegal logging that plagues the area; and the much-loved Balsa tree, the lightest known wood, Ochroma pyramidale, which contributes to regenerating the rainforest.

Ceiba pentandra

Balsa – Ochroma pyramidale

At our forest camp, Dr. Cerón explained that the origin location of plants is indicated by where a botanical family has the highest concentration of species. Nowhere else has he seen such a dense assemblage of plants in the Malvaceae family. He confirmed, “We have made a most impressive discovery. This region undeniably is the origin site of Theobroma cacao, the chocolate tree!” On the equator, along the eastern foothills of Cordillera Napo-Galeras, a mountain known in local folklore as the “End-of-the-World-Jaguar Mountain,” is the origin of the Cacao tree.

Other Cacao relatives from Central & South America

Note: Pictures Credits go to Jim West of Guaycuyacu Seeds. Theobroma microcarpum by The Field Museum, and the last 6 by the author)

Herrania nycterodendron

Theobroma mammosum

Theobroma speciosum

Pachira almirajo

Theobroma sp

Theobroma microcarpum

T. microcarpum

T. angustifolium

T. simiarum

T. grandiflorum

T. bicolor

Cacao varieties

There are reportedly over 2000 varieties of Cacao, very little is still known.

Trinitario

Ruby /

Criollo Chuno

Criollo Tetachola

Criollo

Criollo

Criollo Forastero

Picture by Arcelia Gallardo

She Has Come a Long Way

We now know that Cacao originates in the upper Amazon at the base of the Andes in northwestern South America. How she became such an intricate part of Central America is mostly unknown. She was carried north, perhaps by nonhuman mammals, or by ancient human traders. Consider the first option—we know that the isthmus of Panama rose out of the sea between 3 and 7 million years ago, opening a land bridge between Central and South America which greatly impacted Earth’s climate. The flow between oceans was blocked which rerouted currents, creating the Gulf Stream, warming the planet and provoking a surge in biological diversity. So began the Great American Interchange, where animals and plants migrated between South America and North America. Cacao may have been steadily moved by monkeys, rodents, and other mammals who adore its sweet pulp but leave behind the bitter seeds, slowly spreading North, East, South and West.

Geneticist Omar E. Cornejo demonstrated that the oldest known domesticated Cacao strains in Central America actually originate in the Amazon. Central American peoples cultivated strains of Cacao that had been domesticated in the upper Amazon by Mayo-Chinchipe people thousands of years prior. We know very little about the vanished Mayo-Chinchipe, an elaborate and ceremonial culture that lived for 4000 years at the base of the Andes, along the equator, in the wettest and most biodiverse part of the planet. At the Santa Ana-La Florida archeological site in southeastern Ecuador, Claire Lanaud and Rey Loor dated residues found in stone and clay vessels as far back as 5500 years—the oldest-known evidence of Cacao use.

Cacao utensils from Mayo-Chinchipe culture

Mayo-Chinchipe

Mayo-Chinchipe

Mayo-Chinchipe

Mayo-Chinchipe

Spondylus and Strombus sea shells found at La Florida indicate there was trade between the Mayo-Chinchipe and coastal societies. Coastal peoples of ancient America were navigators and avid wanderers who traded knowledge and goods such as plant materials, salt, gold, and jade pendants up and down the Pacific coastline.

Spondylus shell

Strombus shell

Recent studies by Smithsonian archeologists of pottery on display at the National Museum of the American Indian reveal that Cacao was consumed as far north as the Pueblo Bonito site in the Chaco Canyon of New Mexico.

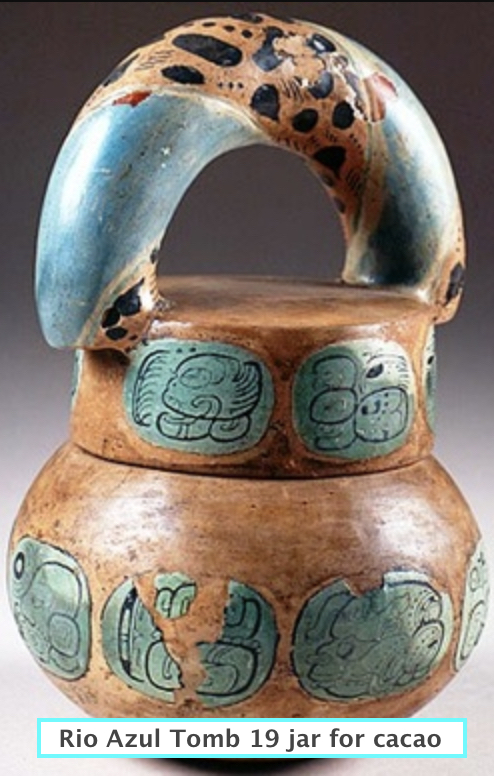

Over 3800 years ago in Central America, Olmec people began cultivating Cacao, which they called Kakawa in their language that seems to be of the Mixe-Zoque family. Though far younger than the Amazonian Mayo-Chinchipe people, the Olmecs were one of the Mesoamerican mother cultures, remembered by colossal stone head carvings and less recognized as the Cacao connoisseurs that they were.

Olmec wrestler

Olmac jade pectoral

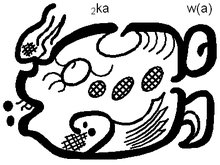

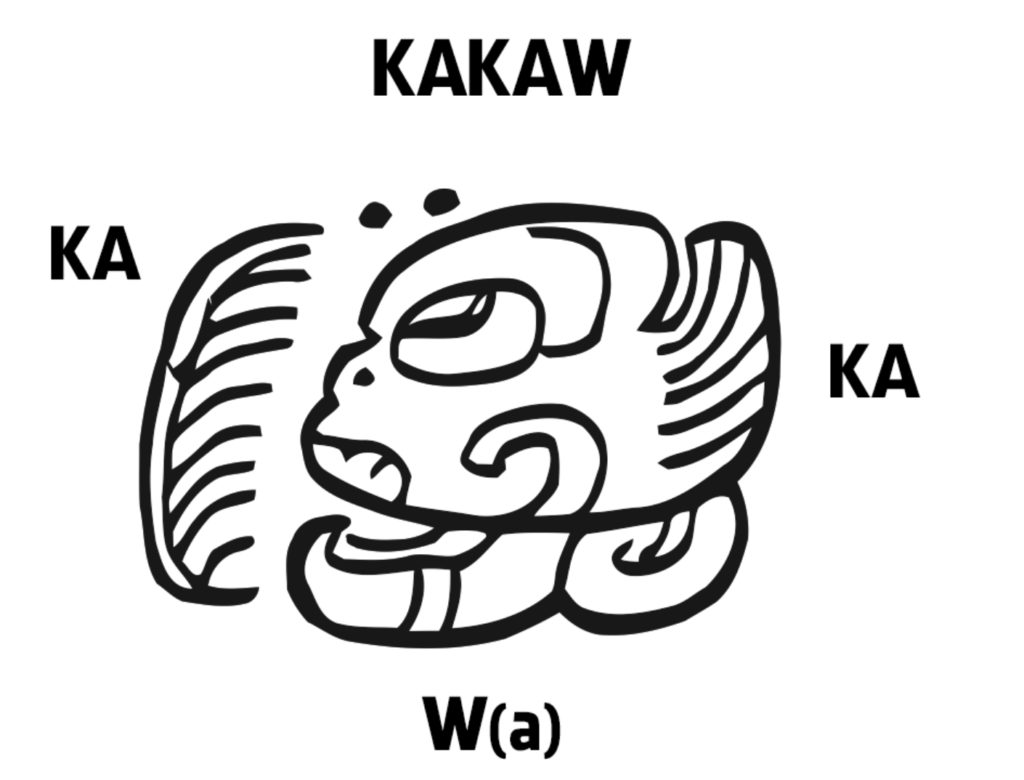

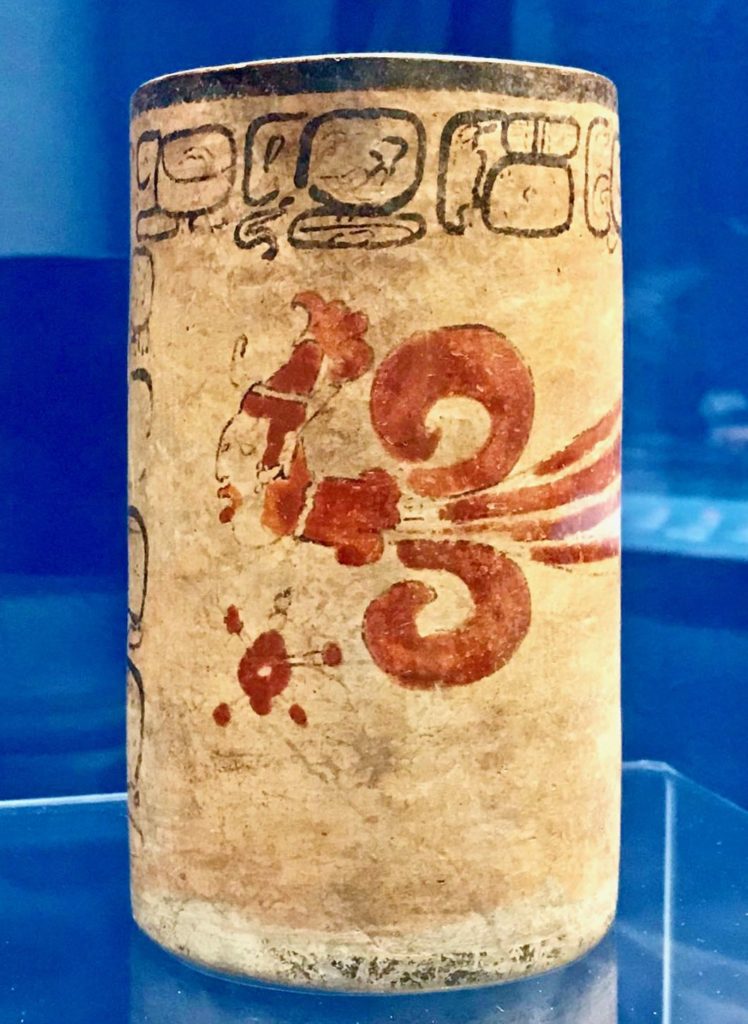

From the Olmecs, the Mayas learned skills including jade carving and the cultivation and use of this fascinating plant. The Mayas adopted the Olmec name and glyph of Cacao, which shows a head with a fish fin ear looking up, with another fin before the glyph’s main features to double accentuate the concept. The word “kakawa” sounds like the Mayan phrase “two fish.”

Mayan Cacao vase (photo by Tulsi)

Segment from a Mayan vase

Cultural anthropologist Dr. Michael J. Grofe, in his paper “The Recipe for Rebirth: Cacao as Fish in the Mythology and Symbolism of the Ancient Maya,” illuminates a parallel between the self-sacrifice of the Hero Twins, depicted in the the Popol Vuh, and the processing of Cacao. The Hero Twins’ entrance into the underworld represents burial and fermentation of Cacao seeds; their burning is the roasting; the grinding of their bones is Cacao seeds ground on a metate, a stone mortar; and their being poured into water represents hydrating the fermented, dried, roasted and ground Cacao into a beverage. The twins are reborn as two fish, offering a provocative insight into the metaphor of Cacao as a potent symbol for rebirth, movement, and water. Fins allow a fish to swiftly move through water as Cacao allows a person to swiftly rise, and Cacao grows in the regions of highest rainfall. The Maya adored Cacao as a primordial element of their way of life, calling it the “World Tree” and the “First Tree.” The Mayan beverage chocol’ha gave rise to the modern word, “chocolate.”

The Hero twins of the Popol Vuh, Huhnapú e Ixbalanqué.

Maya ceramic vase image from Lacambalam

Cacao ~ the Ultimate Superfood

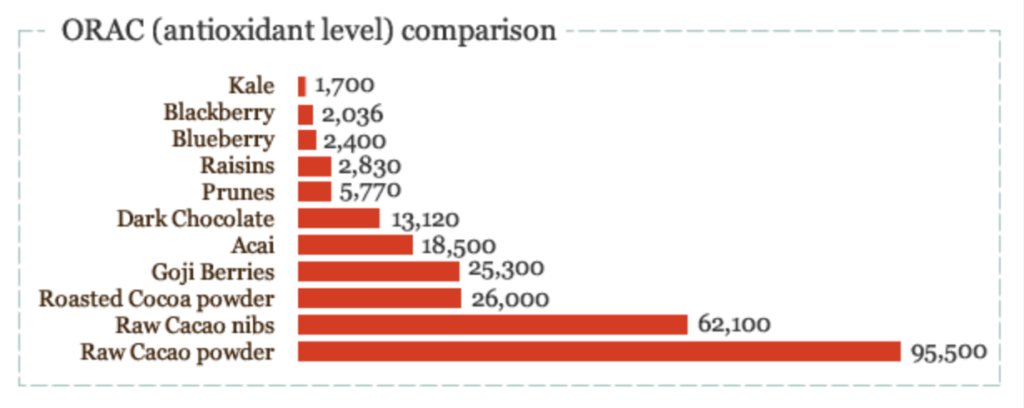

As full as Cacao is with cultural lore and history, it is with nutrients and minerals. Containing anandamide, a chemical that has almost identical makeup as THC, known as the “bliss molecule,” is why drinking Cacao makes you feel happier, while boosting your energy levels. Another peculiar alkaloid in Cacao is theobromine, having similar components as caffeine, but working more on relaxing our hearts. Cacao is also rich in phenethylamine, another alkaloid that our bodies transforms into serotonin, that has been come to be known as the “good mood hormone,” that helps alleviate depression. Cacao’s flavonoids make for an ally in the health of the heart, combating heart disease by mending degradation caused by free radicals. These same flavonoids also aid in lowering blood pressure and act as a blood thinner preventing the risk of blood clots.

Studies have also shown that Cacao can help people who have diabetes. It does this by lowering blood glucose and boosting insulin function, thus stabilizing blood sugar levels. We all know the virtues of antioxidants. Studies have shown raw Cacao to have the highest known antioxidant levels of any known food supplement. Helping rid the body of free radicals that can lead to cancer. Cacao has also been shown to boost blood flow to the brain. More blood to the brain equals more oxygen to the brain, thus, people who eat pure raw cacao score better on memory tests. Ahh Cacao, indeed, the ultimate superfood!

Fallen from Her State of Grace

By the mid 17th century, Cacao, introduced to Europe by the Spanish, became a popular beverage. Plantations were established along tropical coastal regions of Africa. Today, West Africa is the world-leading producer of Cacao, at no light expense. In the early 21st century, Cacao production increased both in Africa and Tropical America by 50%. The story of Cacao production in Africa is sadly not heart-warming, in ironic contrast to the effects of the chocolate that comes from them. UNICEF estimates that there are over 200,000 children working in cocoa plantations in Ivory Coast. Others sources state even higher! Rural exodus in Africa represents more than 60% of the population, the majority of these refugees being youth who fall as easy prey. Meanwhile, indigenous farmers producing Cacao live in extreme poverty, obliged to rely on child labor to serve giant corporations supplying Western demand. Despite the 2001 Harkin-Engel Protocol, an agreement signed by major chocolate companies restricting the use of children to harvest cocoa beans, the crisis is still in full swing. ClassAction.org shares in-depth information on current lawsuits filed against Hershey, Mars and Nestlé, alleging that confectioners have deceived consumers into “unwittingly supporting child and slave labor themselves through their product purchases.”

In Ecuador, the origin place of Cacao, the tree is cultivated in the wettest regions at the base of the Andes, the pinnacle of biodiversity. In western Ecuador, the Tropical Wet Forest has been almost completely obliterated for Cacao monoculture plantations, that now also suffers from blight.

Two of the finest botanists on earth, Alwyn Gentry and Callaway Dodson, wrote about this in their article, “Biological Extinction in Western Ecuador.” In a small protected forest in western Ecuador, at the Rio Palenque Science Center, Dr. Dodson affirms that there are more species of wild Cacao protected there than at any other location on the planet. Despite the importance of conservation of the Tropical Wet Forest, big chocolate companies invest little back into protecting the gene bank of Cacao or improving the quality life of their farmers. Deforestation of critical hot spots of mega-biodiversity and the crisis of childhood slavery on these plantations marks the dismal state that humanity has fallen in to. The Tropical Wet Forest is at the mercy of consumers—we must consciously step up and source Cacao appropriately, and not contribute to this nightmare.

Coming Back Around to an Ancient Future

Driven by a passion for Cacao as a sacred crop, more and more small chocolate-producing companies are transforming the landscape. Appropriately-sourced Cacao is filled with the zest of life, rich in antioxidants and minerals, and highly beneficial for human health. Cacao originates in the most biodiverse environment, not to be grown in monocultural plantations, but rather as a member of a diversified garden system. Kallari, as a case example, is an Indigenous people’s farmer-owned Cacao cooperative in Amazonian Ecuador, whose mission is, “to sustainably improve the economic conditions of local partners and producers through the production, transformation and marketing of mixed agricultural garden products, called chakras, while urging for the preservation of culture and the environment.” Cacao calls for an integral restoration and regeneration of humanity’s relationship with nature, with the Earth, among people and with our selves. She lends herself as a conduit for an ancient future, one that reaches forward to heal landscapes and redirects our present course by inspiring unity of ancient wisdom with the best of modern-day science.

Her Cloak of Universal Wisdom

Cacao’s teaching are clear for all to see. Born at the summit of biological megadiversity, she exhorts that we must reach the peak of consciousness—to feel the joys and sorrows of others and of nature as if they were our very own. She teaches that without biological and cultural diversity, we parch the earth of her essence. That the Earth’s divine abundance slips between our fingers back into the void, if taken for granted. This abundance that blesses so many must be cultivated. She gives and wants us to give back. In her silent invigorating essence, she whispers a vital message: Return to a heart-centered way of reciprocity. Who does not serve, does not live. She holds this truth, trembling with humility and compassion, uneased that we risk failing to see things for how they simply are. That we might fall short in awakening our hearts to universal love and appropriate righteous passion, so needed for us to grow, heal and create solutions. These are the healing salves allowing us to remedy the economic, socio-cultural, and ecological wounds suppressing humanity and the Earth. Without diversity, there cannot be fertility, nor stability; the triad is fluent and indivisible.

In The Diversity of Life, ecologist E.O. Wilson stated, “The sixth great extinction spasm of geological time is upon us, grace of mankind. Earth has at last acquired a force that can break the crucible of biodiversity.” We also face tremendous cultural erosion as languages fade from memory.

Cacao whispers a subtle warning: If we don’t evolve, we risk certain catastrophe. She has witnessed the rise and fall of many societies and cautions of apocalypse. From the ancient perspective of the animistic worldview that sees all beings as having a sentient and energetic soul, I imagine that the meditation mat of Kakawa is revealed, in its brilliant patterns highlighted in golden yellow and neon blue. Streaks of richly-saturated sapphire, emerald green, glowing red, yellow and silver white light swiftly blow around all sides. And there are people sitting upon this mat reflecting upon all that Kakawa teaches. And these people are inspired to rise in alignment with universal order, becoming allies to life, being truly human—awake in our fullest potential.

THE MIND OF PLANTS

This article was written as a contribution The Mind of Plants. edited and compiled by PATRICIA VIEIRA, JOHN CHARLES RYAN and MONICA GAGLIANO, and now in publishing stage. “The Mind of Plants brings together a collection of short essays, narratives and poetry on plants and their interaction with humans. Authors from the humanities, social sciences and natural sciences write about their connection to a particular plant, reflecting upon their research on plant studies in a style accessible for a general audience.”

Links a references

Cacao Mama – History and Spirit of Cacao

National Geographic – Chocolate to Save Forests?

Experience Cacao Ceremony – Firefly Chocolate

Cacao: The Mayan “Food of the Gods”

Is Criollo Really King? The Myth of Cacao’s Three Varieties

The Criollo cacao tree (Theobroma cacao L.): a review

Cacao varieties and its climatic requirements

The UWI – University of West Indies Cocoa Research Center: With over 2000 varieties, the cocoa gene bank is the largest in the world.

List of plants in the family Malvaceae

Ek Chuah (God M) – Mayan Cacao God

UNESCO – Mayo Chinchipe – Marañón archaeological landscape

Cocoa Pest & Disease Management – Best Known Practice

Child slavery in cocoa plantations in Ivory Coast and other African countries: can we prevent it?